Discover why 5-cylinder engines are so rare today, from carburetor problems to the dominance of turbocharged 4-cylinder engines.

The Fascinating Origins of 5-Cylinder Engines in the Automotive Industry

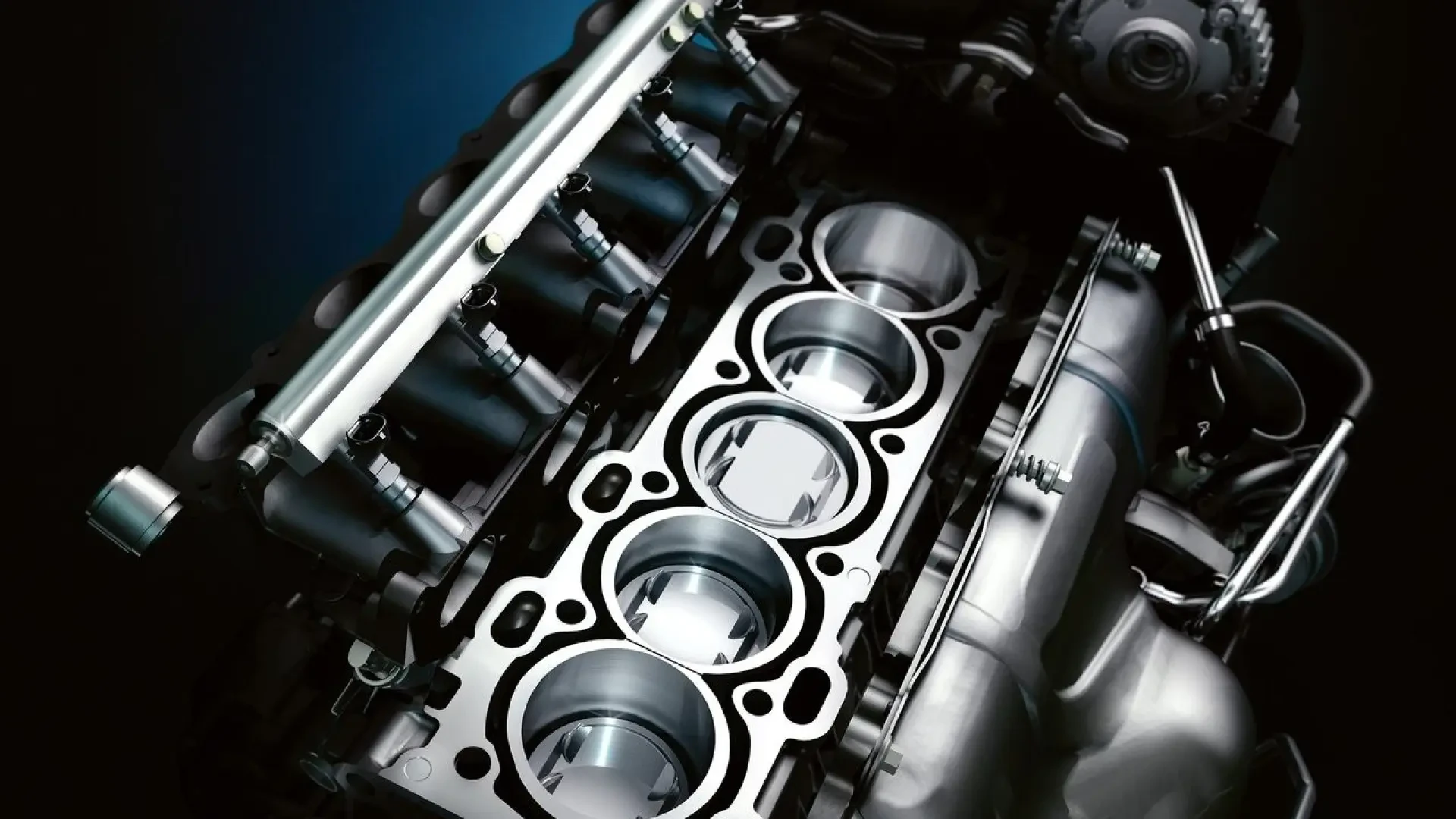

In the vast universe of automotive engines, configurations like 4, 6, or 8 cylinders dominate the market, but 5-cylinder engines have always been an intriguing rarity. Pioneers like Mercedes-Benz in the 1970s sought to balance power and weight by adding just one extra cylinder to a 4-cylinder block to avoid the burden of a full V6. At first, that approach worked, but technical challenges relegated them to obscurity. Today, models like the Audi RS 3 (2026) keep that tradition alive — but why did they largely disappear?

Imagine Mercedes-Benz engineers in 1974, pressured by the oil crisis and tightening emissions regulations. A 4-cylinder engine was light and economical but too weak for premium cars. A V6 added too much weight and complexity. The solution? An inline-5, sharing components with the 4-cylinder but delivering 20–30% more torque. The result was the legendary 2.0L 5-cylinder used in some Mercedes models, which offered a unique vibrational smoothness — thanks to its irregular firing intervals that created an addictive, guttural sound nicknamed the “five-cylinder symphony.”

However, this configuration never became globally popular. Brands like Volvo, Ford and Audi experimented in the 1980s and 1990s, but production volumes were low. To understand the rarity, look at the data: less than 1% of current vehicles use five cylinders, versus roughly 60% using turbocharged four-cylinder engines. If you enjoy stories of Mercedes-Benz’s iconic engines, this is one of the most underrated.

Problems with Carburetors and Early Fuel Injection

One of the biggest barriers for 5-cylinder engines came from the pre-electronic injection era. Before the 1990s, carburetors were the standard for mixing air and fuel. In even-numbered engines (4 or 6 cylinders), it was easy to configure: two carbs for four ports or one carb per bank in a V6. But with 5 cylinders, the odd number created chaos.

- Single-carb setup: A central carburetor would feed cylinders unevenly, with the middle ones getting more flow while the outer ones were starved.

- Multiple carbs: Three carbs? Impractical due to asymmetry — two feeding three cylinders and one feeding two would create pressure imbalance and unstable RPMs.

- Complex engineering: Solutions like custom manifolds or siamese carbs existed, but raised costs by 30–50%, negating the intended savings.

This caused efficiency losses: up to 15% less power at low RPM and higher fuel consumption. The shift to single-point injection did little to help; only multi-point injection (one injector per cylinder, controlled by an ECU) balanced things in the 1990s. Scandinavian brands like Volvo persisted with tuned carbs on models such as the 850R, but the added cost limited adoption. For those who want to dive into evolutions of ignition systems, 5-cylinders were collateral victims of that revolution.

| Comparison: Inline-5 Engines vs Competitors (1980s) | Average Power (hp) | Weight (kg) | Production Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 Cylinders (Mercedes 2.5L) | 150-180 | 160 | High |

| 4-Cylinder Turbo (Ford 2.3L) | 160-200 | 140 | Medium |

| 6-Cylinder Naturally Aspirated (BMW 2.5L) | 170 | 190 | High |

The table above illustrates the dilemma: 5-cylinders beat naturally aspirated fours in low-end torque (ideal for diesels like the Audi 100 TDI), but lost to emerging turbocharged fours on cost-effectiveness.

The Dominance of Turbos: Why Five-Cylinder Engines Became a Relic

From the 1980s onward, turbochargers changed the game. Invented in the early 1900s by Mercedes for aviation, they only matured for road cars in the 1970s. A 2.0L four-cylinder with a single-scroll turbo can deliver 250–300 hp today, at roughly 20% less weight than an equivalent naturally aspirated five-cylinder.

“Turbos turned downsizing into superpower: a modern 4-cyl turbo rivals old V8s without the extra vibrations.”

Advances like sequential twin-turbo systems (used on the Porsche 911 Turbo), electronic wastegates and more efficient intercoolers eliminated lag and increased durability. Examples? The Ford EcoBoost 2.3L in the Mustang makes 310 hp with relatively low emissions. For 5-cylinders, turbocharging helped (the Audi Quattro five-cylinder dominated 1980s rallying), but it didn’t save them: why complicate the lineup with a larger block if a turbocharged four-cylinder is enough?

- Efficiency: Turbos boost power by 40–60% without adding cylinders, often reducing weight by about 50 kg (≈110 lb).

- Emissions: Euro 6/7 standards favor downsizing; naturally aspirated five-cylinders generally emit more.

- Cost/OEM: Modular platforms (VW MQB) optimize four- and six-cylinder layouts, sidelining five-cylinder designs.

Today, survivors include the Audi RS3/RS Q8 2.5 TFSI (400 hp, 0–100 km/h or 0–62 mph in 3.8 s) and older Volvo V60 Polestar models. But electric and hybrid powertrains promise further decline: understand how compression and turbo evolved. In Brazil, imports like the RS3 cost over R$800k, but the unique sound still draws enthusiasts.

Looking to the future, 5-cylinders could be reborn in off-road niches or as heritage-sound engines, with persistent rumors of a hybrid Mercedes-AMG unit. Meanwhile, three- and four-cylinder turbos dominate: the GR Corolla’s 1.6L turbo (304 hp) proves that small can be mighty. Curious about block materials that influenced this? The shift to lightweight aluminum sealed the fate of heavier five-cylinder blocks.

The rarity of five-cylinder engines stems from historical incompatibilities and modern demands for efficiency. Yet their unmistakable rumble guarantees a lasting cult following among gearheads. For more, check ignition secrets in modern engines and how less can be more.