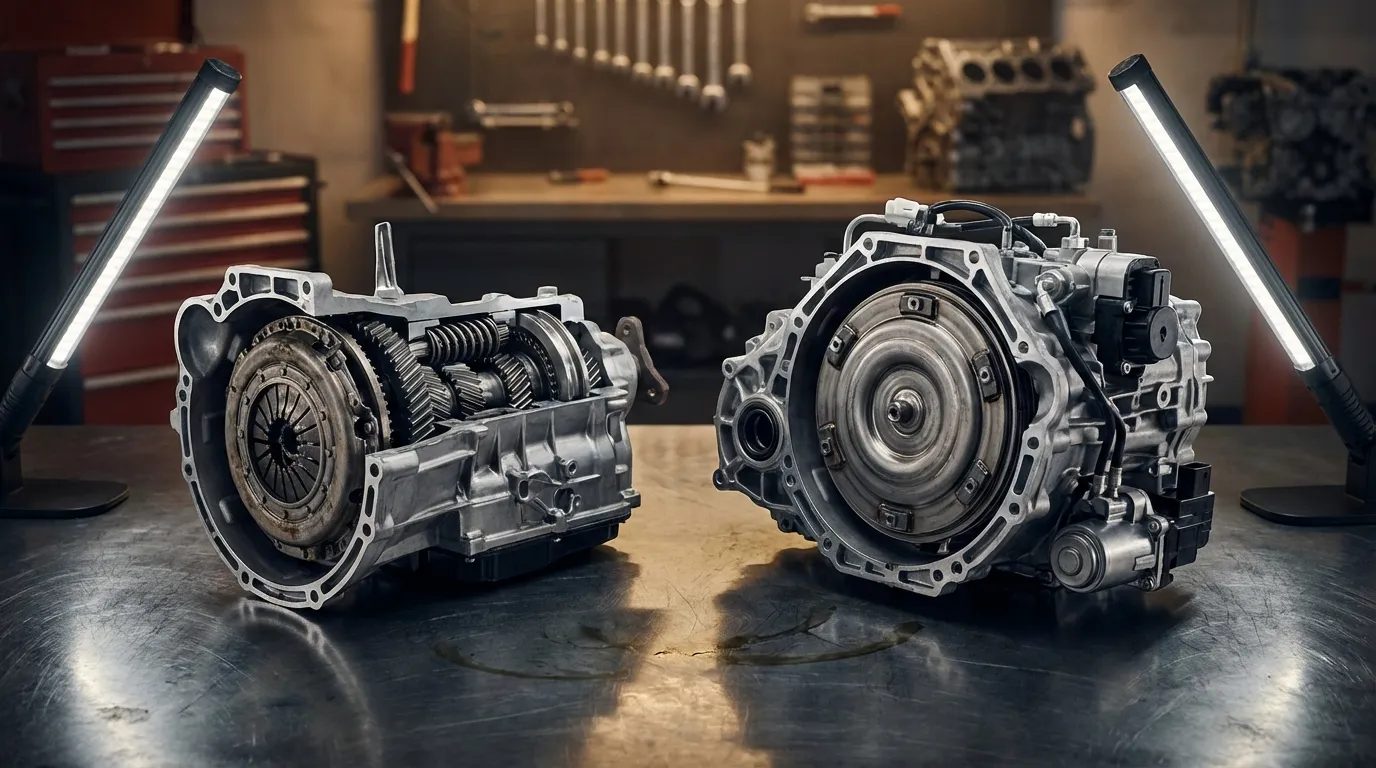

See the difference between single-clutch and dual-clutch transmissions, how they work, advantages, disadvantages, and which one to choose for your driving style.

You might even call everything “automatic,” but there is a detail that completely changes the driving experience (and the cost when maintenance is due): the fundamental difference between single-clutch and dual-clutch transmissions (DCT).

What Is a Single-Clutch Transmission and What Is a Dual-Clutch (DCT)?

To understand the difference between a single- and a dual-clutch transmission without unnecessary technical jargon, think of it this way: every transmission needs to “negotiate” the engine’s torque with the wheels. This negotiation happens through the clutch (or clutches) and the set of gears.

The Single Clutch is the traditional setup: one clutch assembly to connect and disconnect the engine from the transmission. The Dual Clutch (DCT) uses two clutches working in alternation to leave the next gear “ready” even before you perceive the shift happening.

The practical result is a very clear contrast:

- Single Clutch: Gear shifting depends on disengaging, selecting, and re-engaging. It can be fully manual (with pedal) or automated (with actuators).

- Dual Clutch (DCT): One clutch manages the odd gears and the other manages the even gears, allowing for pre-selection and extremely quick shifts.

If you are interested in the “geeky” mechanics, it’s worth connecting this topic with the evolution of systems that made engines more efficient and reliable. A classic example is how ignition moved from distributors to individual coils: the change that made engines stronger and more economical. In transmissions, the logic is similar: more electronic control equals more precision and better performance.

The Basics of the Clutch: The “Switch” Between Engine and Wheels

In any vehicle equipped with a clutch, the engine spins a flywheel, and the clutch controls when this rotation passes to the transmission input shaft. In simple terms, the clutch is a “friction sandwich”: when engaged, it “glues” the engine and transmission together; when disengaged, it separates the two to allow gear changes without fighting against engine speeds.

When synchronization fails (especially in manuals), the infamous gear grinding occurs. In a DCT, electronics strive to prevent this by managing the clutches with far more precision and repeatability than a human foot in Monday morning traffic.

How a Single Clutch Selects Gears

In a single-clutch setup, gears are arranged sequentially: 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and so on. The typical shifting process involves:

- Disengaging the engine from the gearbox (clutch pedal pressed or system disengages automatically);

- Selecting the new gear (via gear lever or electro-hydraulic actuators);

- Re-engaging the clutch and resuming torque transfer.

This process can be engaging (for those who enjoy driving) and mechanically simple. However, “simple” doesn’t always mean “cheap”: harsh use, excessive heat, driving with your foot resting on the pedal, and heavy traffic will wear out the clutch sooner. If you want to avoid unpleasant surprises, it’s worth reading this straight-to-the-point guide: maintenance errors making your mechanic rich and putting your safety at risk.

How the Dual Clutch (DCT) Shifts Gears So Fast

The DCT functions as if there are two separate power paths inside the same gearbox housing:

- One clutch manages the odd gears (1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th…);

- The other manages the even gears (2nd, 4th, 6th…).

While you are accelerating in 3rd gear, for example, the system may already have 4th gear selected on the other path, spinning at the necessary rate. During the shift, it executes a coordinated movement: one clutch opens as the other closes, virtually without interrupting torque. This creates the common feeling of a “continuous pull” and shifts occurring in milliseconds.

This setup also explains a trick that a single clutch cannot perform as smoothly: skipping gears under specific conditions (e.g., downshifting quickly from 6th to 3rd) because the transmission has two parallel sets, allowing electronics to plan the seamless engagement.

DCT Is Not a Traditional Automatic: The Costly Confusion

Many drivers refer to DCTs as “automatic,” and they can feature an automatic mode, but the underlying design differs from the classic automatic transmission. The traditional automatic generally relies on a torque converter and a planetary gear set, employing a different philosophy regarding smoothness and coupling.

Here is a quick rule of thumb:

- DCT: More direct, fast, “mechanical” feel, excellent for performance, potentially more “nervous” at low speeds depending on tuning.

- Traditional Automatic: Generally smoother in low-speed maneuvers and city traffic, exhibiting more “slip” at the converter (which often aids comfort).

This difference is very apparent in urban driving: a DCT might give the impression of constantly “engaging and disengaging” in stop-and-go traffic because it modulates the physical clutches (actual friction), unlike the torque converter which multiplies torque via fluid.

Advantages and Disadvantages: Real-Life Differences

The prevailing question isn’t just “what’s the difference,” but which transmission is better suited for my needs. The answer depends heavily on your typical usage, the vehicle type, and your tolerance for specific operational behaviors.

| Criteria | Single Clutch | Dual Clutch (DCT) |

|---|---|---|

| Gear Shift Speed | Slower (depends on driver skill or actuators) | Very fast, featuring pre-selection capability |

| Driving Connection | High in manual mode; variable in automated versions | High, direct, and sporty driving feel |

| Traffic & Maneuvers | Manual version can be tiring; automated versions vary | Can be less smooth at low speeds (design dependent) |

| Efficiency | Good when driven well manually | Usually excellent, with minimal torque interruption |

| Complexity | Mechanically simpler | More complex (involving multiple clutches and electronic control) |

| Maintenance Cost | More predictable tendency | Potentially high depending on parts, specialized fluids, and labor |

When a Single Clutch Makes More Sense

- If you demand complete control: A manual single-clutch setup is often unbeatable for the “I am in charge” sensation.

- If your usage is mixed and you accept the physical wear associated with heavy traffic use (the pedal).

- If you prioritize robustness and predictability: Fewer sensors, fewer actuators, fewer variables to monitor.

However, be mindful: driving well also means caring for the system. Some habits you might think are “economical” actually lead to mechanical damage, such as leaving the car in neutral while going downhill. If this is part of your routine, it is vital to understand why: the myth about fuel economy that can potentially destroy your car’s engine.

When DCT Is the Superior Choice

- If maximum performance is your goal: Fast shifts, strong acceleration response, and a feeling of continuous power delivery.

- If you enjoy driving actively: Utilizing paddle shifters and manual mode without needing a clutch pedal.

- If you switch between comfort and sportiness: Automatic mode for daily commuting, manual mode for spirited driving.

It is no coincidence that DCTs are commonly found in sports cars and performance-oriented trims. And when the discussion turns to “real cars,” performance often brings other mechanical obsessions, such as legendary engines. If you appreciate that visceral side of motoring, you will enjoy this list: all production cars equipped with the Hellcat engine.

The “Flaws” Nobody Mentions (That Become Common Gossip in Online Groups)

Some operational quirks are normal, while others signal a need for attention. The challenge is that online, every minor behavior can be mislabeled as a “faulty transmission.” Here is what genuinely warrants consideration:

- Vibration upon initial takeoff: Can occur in DCTs (especially those with dry clutches) due to wear, overheating, or poor calibration.

- Shuddering at low speeds: Common in certain DCTs during stop-and-go traffic because the system is actively modulating the clutch friction. This isn’t necessarily a defect.

- Delay engaging Reverse or Drive: May signal a need for system adaptation, correct fluid level/quality, or an issue with actuators/solenoids depending on the specific design.

- Clutch odor: Present in both DCTs and single-clutch systems. In a DCT, it appears often when the car is heavily stressed on inclines, during prolonged low-speed maneuvers, or in heavy traffic.

If you frequently drive in hot climates, navigate mountain passes, carry heavy loads, or constantly manage tight parking spaces, these operational details become more critical. And there is one factor almost no one observes: heat is the silent enemy of many automotive systems—it affects the engine, the transmission, and even basic daily items. A good analogy involves tires: when inflation is set based on guesswork, it ignores the critical truth that can save your car.

How to Choose Between Single and Dual Clutch Without Falling for Traps

If you aim to make a safe decision, follow this practical checklist. It applies equally well to both new and used vehicle purchases.

Quick Checklist Before Purchasing

- Is 70% of your driving city traffic? A DCT might become annoying (and prone to overheating) depending on the specific model. Always conduct a test drive replicating real city conditions.

- Do you plan to keep the car for many years? Thoroughly research the costs associated with clutch replacement, mechatronics/actuators, and specialized fluid changes.

- Does the transmission system have a documented service history? For DCTs, using the correct fluid and adhering strictly to replacement intervals is crucial.

- Do you frequently drive on steep ramps or in parking garages? Check how well the car “holds” on inclines and if the release is progressive without unusual smells or shimmying.

- Is driving enjoyment your priority? If rapid shifts and paddle control appeal to you, a DCT generally delivers more smiles per mile.

Golden Tip for DCT Daily Use (To Reduce Wear)

Avoid “holding” the vehicle on an incline for extended periods using only the accelerator. Utilize the brakes or the auto-hold feature when available, opting for straightforward stop-and-go maneuvers. This habit in a DCT significantly reduces clutch slip, heat generation, and premature wear.

Simple Rule: If you are causing the car to move slowly for prolonged durations solely by applying minimal accelerator pressure, the clutch is bearing the cost.

What to Ask the Mechanic (Or Specialized Shop) Without Seeming Uninformed

- “Is this DCT a dry clutch or an oil-bathed clutch system?”

- “What is the specified fluid, and what is the actual replacement interval for this specific gearbox?”

- “Is there a mandatory adaptation procedure required after replacing components or updating software?”

- “What are the typical early symptoms when this particular model begins to show wear?”

These questions quickly differentiate between a technician who understands complex transmissions and someone who merely clears fault codes from the scanner. And since we are discussing avoiding pitfalls, there is a seemingly minor detail that severely damages resale value and becomes a nuisance during inspections: the invisible enemies destroying your car’s value.

Honest Summary: What Truly Changes

- Single Clutch acts as “a physical bridge” between the engine and gearbox: it disconnects, shifts, and reconnects. It is mechanically simple, direct, and offers more predictable maintenance.

- DCT functions like “two alternating bridges”: while one transmits power, the other simultaneously prepares the next gear ratio. The result is rapid shifting, a sporty feel, but greater inherent complexity requiring diligent maintenance.

Ultimately, the difference between single- and dual-clutch transmissions is not just about “one extra clutch”: it represents an entirely different philosophy regarding how the vehicle manages, prepares, and delivers torque. And that difference is precisely what you feel through your foot, the steering wheel, and, in certain cases, directly in your maintenance budget.